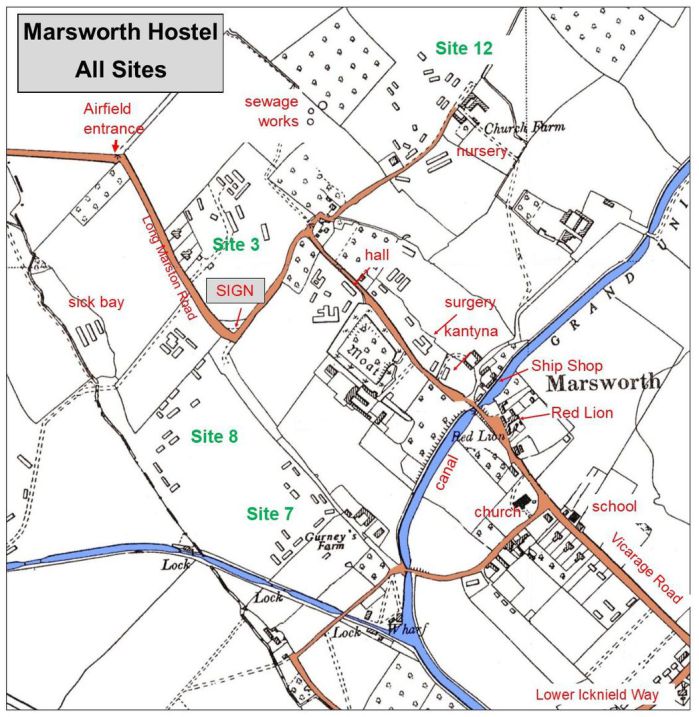

Life at Marsworth Hostel

EVERYDAY LIFE AT THE HOSTEL

Compiled by Barbara Fryc, with additions from people who lived there.

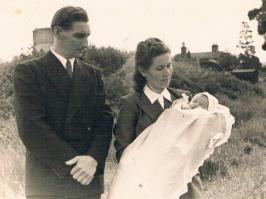

While Barbara was not a resident at Marsworth Hostel, she spent

her early childhood at another Polish camp where conditions were very similar.

Food

At first meals were provided and served at the communal dining hall. There was also a separate canteen which served drinks/snacks, beer, etc. People could eat together in the dining hall or take their food to eat in their huts. Everything was rationed and everyone had cards.

Additional food was grown by some; it gave them purpose and satisfaction, in particular those who had been farmers or had grown their own food before the war. The land around the barracks had been agricultural land so little plots and allotments were created. Here they grew vegetables and some grew their own tobacco, perhaps having brought seeds from Africa.

Wojciech Winnik outside his barrack at Site 12 showing garden of flowers and vegetables

.

Flowers were also grown and used to decorate the huts and the communal areas at dances and in the Hostel chapel.

When people got their own ration books they were able to do their own cooking. Some family barracks had small cookers installed and would cook up Polish specialities and even bake – those who knew how and had learned from parents or grandparents.

At first the furniture was the remnants from the military camp - plain basic cupboards and wardrobes - wood or metal tables and chairs, army style beds (metal frame with horsehair mattresses, metal wire base with springs). Some families were lucky to have proper wooden frame beds obtained through the National Assistance Board (NAB) from furniture donated alter the war.

Many people took this furniture with them when they left the camp to live in towns and cities, until they could afford their own furniture. In time, second hand furniture was also obtained.

Cutlery and crockery were basic as at the beginning food was cooked in a canteen and people ate together; as rationing ended, barracks had cookers installed and people cooked their own. Supplies and foodstuffs were brought into the camp weekly by local suppliers.

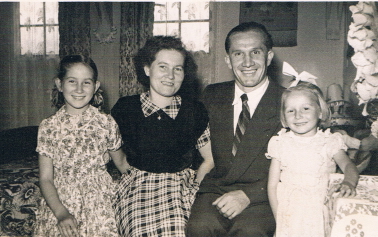

Families made the barracks homely by buying colourful curtains and tablecloths, with pictures and photographs on the walls or homemade Polish craftwork such as patchwork quilts and mats made from fabric remnants. Many talented artists and artisans developed their skills and produced articles.

Huts were decorated in a traditional Polish way to make them homely.

Personal Hygiene

Amenities were basic. There were shower and toilet blocks for each site which were shared. To wash, bowls were used or a tin bath to wash the children in; if there were a few children the same bath water would be used, just topped up with hot water.

Hot water was made available twice a week for washing clothes and laundry in the wash houses. Here washing was done by hand, using a wash board and tin bath in the barrack, or the proper sinks in the wash blocks which also had boilers and mangles which were used to press sheets, towels/blankets etc.

Toilet blocks were located around the camp.

The toilets in the block were numbered on the cubicle doors with the same number as the hut, so each one was for the use of that family. In practice a chamber pot was used at night by adults and children and then emptied at the toilet block the next day.

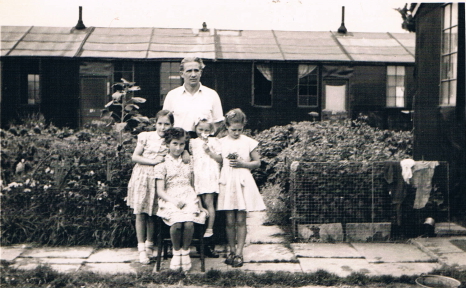

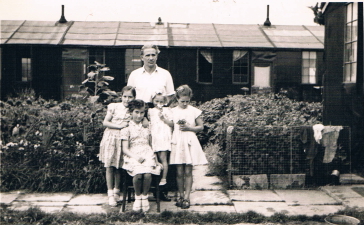

Group with washhouse behind

Cyganek family with washhouse behind

Washing was hung up near each barrack or in the wash house where there were wooden racks and washing lines - good on a rainy day. Personal washing was usually hung in the barracks.

Group at Site 12 with washing behind

Education

The adults at the hostel included ex-Polish soldiers who had fought with the British and Americans and other Allies in WWII. These men and women knew some English and other languages - Polish, French, German, Russian, but English was the language they all needed to learn proficiently to get jobs and live in England. Many had been professional people before the war, such as doctors, nurses and teachers. However many had been manual workers who hadn't had the opportunity to acquire skills except those that the army, navy and air force had trained them in.

Others had very limited education, such as the older people, children aged 9-15 years and young adults who had gone through the war with little education of any kind. They had received some schooling with the Polish Army at the bases of refuge in Palestine, Iran, India and Italy where they were taught to read and write and had completed the basic Polish education level.

School-age children

At Marsworth Hostel there were children of all ages. Some 112 younger ones went to the local Marsworth School between 1950-60; older children went to secondary schools in Aylesbury and Aston Clinton. The children used to travel by bus which collected them at the Icknield Way. Many parents sent their children to Polish private schools such as the convent in Tring or others established after the war by religious orders and the Polish Government in Exile.

Click here to learn more about their schooldays

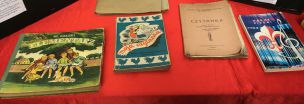

However, while the learning of English was recognised as vital, great emphasis was also placed on promoting the Polish language, history, geography, religion, culture and customs. The great hope was that they would eventually return to a free Poland and the preparation for this return included language and cultural awareness. As a result the SPK (the Polish Ex-Combatants Association) established and sponsored the Polish schools where adults and children were first educated at the hostels/camps.

The first Saturday School in the hostel was set up by the parents, volunteer teachers and the priest - many of the servicemen/women who had been teachers or had a good education before the war taught unpaid in these schools. They included Professor Sobkiewicz, Mrs Puszczynska, Mrs Madras and Mrs Helena Czaczka who was a qualified teacher before the war in Poland and who taught Polish history and language.

Other subjects included singing with Mr Jerzy Jeron and Polish folk dancing; religion, crafts and music. Many talented musicians taught children and adults on piano, violin and accordion. Jerzy Jeron was one such ex-soldier/musician; he established a band that played at the dances at Marsworth, ran the choir and was Parish organist and choir master for over 50 years.

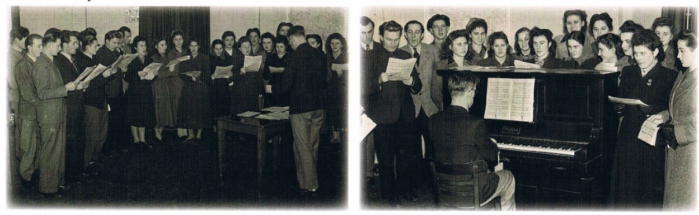

Jerzy Jeron conducting the choir and playing the piano at Marsworth Hostel

Keeping Polish Traditions Alive

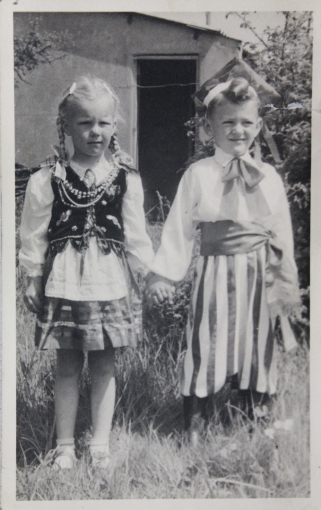

At Polish festivals and concerts, on national days - Constitution Day (3rd May), Independence Day (11th November) and Corpus Christi - children would be dressed in traditional national costume. Availability of materials to make such costumes was limited, however the Hostel residents were very resourceful and creative and were able to make suitable and effective costumes out of fabric bought locally. As boots were hard to get and expensive, shoe covers were made from black furnishing material and worn over normal black shoes to look like boots.

Children learned Polish national dances

QUOTES:

Huts and life in Marsworth Hostel

We first lived in a Nissen hut on site 12. The huts were cold and housed up to three families with rooms separated by blankets or curtaining of some sort. We then moved to Site 7 to a rectangular type of hut; these were known as ‘baraky’ (barracks) and were made of wood, plasterboard and felt. These usually housed three families, with plasterboard partitions. There was a big coke and coal store on the right near the entrance to site 8. The concrete base is still visible.

None of the accommodation had toilets - they were in separate blocks, which were also separate from the washrooms. Lutek Foremniak

Marsworth camp itself was very homely. The little huts, divided between numbered sites, housed two families each. Some were semi-circular Nissen huts, but ours was just an ordinary hut. We affectionately called them ‘barrels of laughter’, I remember that people really liked living in them and there was a great community spirit in the camp.

After Africa, though, it seemed very cold – I had brought many books with me to England and had to burn them all to keep warm.

Mainly, the huts served us very well. They were not luxurious but certainly comfortable, furnished with iron-framed beds, a table and chairs, wardrobe and stove. Anything else we needed could be obtained in the second-hand shop at Tring, or improvised. We had a ‘coffee table’ converted from a wooden packing crate.

Bronislawa Glinska

The huts could be made comfortable and homely

At first meals were cooked in communal areas, but gradually people began to cook for themselves. Bathing and laundry were also communal, there were huge water containers in the camp.

Everything was rationed; we all had cards and supplies were brought into the camp weekly from Tring. No-one went short of anything; we had enough to eat but it was very plain food. There was no waste, a use was found for everything. After a while, we began to establish gardens around the huts. We grew vegetables but some flowers too, which helped the residents feel at home. A lot of us had come from rural backgrounds, so we enjoyed tending our gardens.

Life in the camp was very well organised, and run very much with the wellbeing of the residents in mind. There was a church (chapel), a Polish doctor, and

infirmary.

Bronislawa Glinska

Our home was a hut, situated on Site 7. My mum told me when we first arrived at the camp that there was communal catering, then cast iron range cookers were installed in the huts. They were given ration books and then began catering for themselves.

Our hut was furnished with ex-army iron framed beds, mattresses and bedding, folding chairs, table and wardrobes. The floor was covered with black bitumen; on this my

mum

put some rugs down and in the middle stood a pot-bellied coke-burning stove, with a long flue exiting through the roof. This was the only source of heating; we also acquired some extra paraffin

burning heaters to help with the cold.

There was one large bedroom which was divided into two rooms by a curtain; we also had a bed in the living room which doubled up as a settee.

Jan Baliszewski

For entertainment we listened to the radio and a wind-up record player. We had electricity in the huts, but no running water - mains water was obtained by a stand pipe, which we shared; there were a few on the site.

We had shower and toilet blocks which were shared. The toilets in the block were numbered on the cubicle doors with the same number as the hut; there were also blocks with baths and washrooms for laundry and our huts were clustered around them. These ablution blocks did have hot and cold running water, but were not heated and were very cold in the winter. The hot water was heated by big boilers fuelled by coke on selected days only.

Jan Baliszewski

Huts were heated by a wood burning stove, which was also used for cooking. Water had to be fetched by bucket from elsewhere.

Ted Lyjak

Our barrack had a ‘range’ in the large kitchen. Poles very quickly made the barracks into homes; net curtains, flowers and vegetables planted.

There were communal toilets and baths. I used to take a bath in an iron tub by the ‘range’ and didn't use the baths.

Liz (Elzunia) Oleskiewicz

Families were housed in huts known as barracks. These varied - some were made of wood and covered in bitumen with either an asbestos or metal corrugated roof. Others were Nissen huts - half barrel shaped made from corrugated panels, with metal windows and wooden doors.

There were normally two families to a barrack. They were divided inside - curtains or blankets were used to divide them into rooms for children and parents. Heating was provided by large iron stoves.

Some buildings were made from brick and concrete - these were the wash houses, shower areas, kitchens and canteen, medical accommodation and some administration huts. In addition there was a hall for entertainment and recreation areas.

Barbara Fryc

Allotments, chickens, tobacco etc.

We had on site allotments near to our hut, where my mum and dad liked to grow their own vegetables. They also kept chickens and I loved looking for the eggs. Some

people on site grew their own tobacco - I could see the leaves strung up to dry. The camp’s authorities, pressed by Customs and Excise, did eventually stamp out the practice.

Jan Baliszewski

There were vegetable plots near the canal. Each family would have their own area. My father used to grow tobacco and I used to cut the tobacco for him in the shed. We also kept chickens and rabbits and geese in a chicken and rabbit run, fenced off into family sections, near the boundary near Lock 4. I used to collect dandelion leaves to feed the rabbits.

Lutek Foremniak

Mr Olchowicz used to grow tobacco.

Zig Latyszonek

Work

There were many opportunities for work and local firms took on many people from the Hostel. Officials came to the camp with details of local job vacancies and any work offered was gladly accepted. Some professional people, such as doctors, nurses or teachers, did courses so that they could follow their profession in England, but after the war there were many jobs available for unskilled workers as well.

To get to work some went by coach if their firms provided them. Others travelled by bus, train and bicycles or walked. Others went by motorbike when they could afford one. In time they could learn to drive and then buy a second-hand car. Contacts at work speeded up the learning of English as well as improving knowledge of life outside the Hostel.

Those who were able to work found jobs, mostly at firms based at Apsley, Eaton Bray, Tring, Hemel Hemstead, Pistone, Aylesbury and Leighton Buzzard.

|

The 1952 list of occupants of the Hostel lists all places of employment at that time EMPLOYMENT ANALYSIS – OVER 5 NAMES

|

|

Other places of employment

|

QUOTES:

Work

Immediately after the war we received ‘pocket money’ if unemployed. Officials came to the camp with details of local job vacancies, any work offered was gladly accepted. We knew we had to make our own way and we wanted to settle down, have families and all the usual things in life, so we tried to save as much as possible.

Some professional people, like doctors, nurses or teachers, had to do courses so that they could follow their profession in England, but after the war there were many jobs available for unskilled workers as well. My husband had worked on the railways during the war, so he got a job with British Rail. I worked in a factory; I was a child when the war broke out and unskilled.

Not many people in those days had cars, so to get to work we would take the train from Tring or a local bus, cycle, or walk. My husband cycled to work but later on he learned to drive. Our neighbour by this time had bought a second-hand car, and sometimes gave us a lift to work or the shops.

Bronislawa Glinska

My father worked in Pitstone as an electrician and commuted to work at first by bicycle and then by motorbike. My mother worked at the Eaton Bray clock factory, but I

do not know how she got there. It is possible that my father took her on the motorcycle or she went by local bus.

Stanislaw Jakubas