Parkitna - Krystyna, Lidia and Aniela

This section contains the memories of sisters Krystyna and Lidia at Marsworth Hostel,

and an account by their mother Aniela of her journey from Poland to Marsworth

Krystyna Parkitna

We first met Krystyna (now Kryssie Smith) at the launch of the first edition

of the Marsworth Polish Hostel book, in November 2022.

We asked her for her memories and this is what she sent us, together with the photos.

They are an invaluable addition to our resources.

Memories of Marsworth Polish Camp

I was born in Aylesbury hospital on 9th November 1952 to parents Aniela and Jozef Parkitny and brought home to the Polish Refugee Camp in Marsworth where they lived with my six year old sister, Lidia. This was on Site 8 in Hut 9. It was a typical style RAF barrack divided into three. We were 9A. In the middle in 9B was a childless couple called Bis and at the other end in 9C a family called Antoniak.

I suspect our lives at that point were much the same as the lives of all the other refugees in the camp. Sadly, two and a half years later, my father, aged 45, died. My mother was left a widow with two small children to bring up on her own.

She was an accomplished needlewoman and for a while managed to live on the money my father left and the little income she earned from making or altering clothes for the other people in the camp. About a year later, with my sister already at school, I was sent to the Polish nursery in the camp (at the end of Church Farm Lane) while she went to work in the lipstick factory in Tring at the Silk Mill).

Schooldays

I turned five in November 1957 and it was time to go to school. I barely spoke English. My mother, a devout Roman Catholic, decided to send me with my sister to the convent, St. Francis de Sales, in Tring. Unfortunately, the small legacy my father had left soon ran out and despite the fact that the nuns offered my mum reduced fees for the two of us, staying at the convent became untenable. We were taken out of the convent and Lidia, by now aged 12, went to the Grange in Aylesbury and I started at the local school in Marsworth.

Lidia was picked up by the school bus from outside the Village Hall in the mornings at 8am. I was more of a problem. By now my mother had got a better job as a seamstress in a factory in Berkhamsted making coats for Peter Robinson - a large shop in London. This meant a commute first to Tring, then a change of bus to Berkhamsted. She started work at 8.45. For a while a neighbour, whose son also went to Marsworth School, walked me with her son to school in the mornings and back home in the afternoon and Lidia picked me up when she was brought back by the bus. This didn’t last long however as one by one the neighbours moved away, mostly to Dunstable - when they were able to afford the new houses built on the new estates - or further afield.

Soon there was no one left to watch me. My mother was worried but I was not. “I’ll be fine”, the seven-year-old me told her - and I was. So she and Lidia left just before 8.00. I remained in the hut on my own and was told to watch the clock until it was 8.45 and then to walk to school to get there for 9am. I used to walk through the playing field, cross the canal by the lock and then along the canal, over the two bridges and past the church to end up at the school.

This worked for a while. However the huts were very cold; there was virtually no insulation and when the iron stove was out, the only form of heating was a small paraffin stove. I was always told to make sure I had turned the stove out before I left, and usually that’s what I did.

Unfortunately one day, instead of turning the wick down I must have turned it up. When I got back from school, the ceiling and walls were black with soot where the paraffin had burned out. The whole place smelled of paraffin. Terrified my mother would be angry, I was desperately still trying to wash soot off (which made everything look worse) when she got back from work.

I become the school caretaker

I think that must have been just before my eighth birthday (1960). By then the Hostel was virtually deserted. Only a very few families remained and everyone led their own lives. My mum took me to see the headmaster. By now I was official interpreter and, through me, she explained to him (I’m not sure of his name, maybe Mr. Bell) that she was afraid I would set fire to the hut and asked if it would it be possible for me to come to school early. He agreed.

And that was when I became a school caretaker! Every morning, just before 8am, I would arrive at the headmaster’s house next door to the school and knock on his door. He must have been too shy to allow me to see him in his dressing gown because he would pass out the keys to the school through the letterbox and I would let myself in through the main door.

On cold mornings I would take in all the milk bottles the milkman had left for our break, into the classroom and stand them next to the large iron stove in the corner. I took down all the chairs from the desks where they had been left by the cleaners. I arranged all the books on the shelves in alphabetical order and when the mobile library came round on Thursdays, I chose which books to send back to the library and which new books we should have. And if there was any time left over, I read. I dread to think what Health and Safety would say about that now!

I enjoyed school. When I first started there, aged six, I was one of many Polish children. Gradually, and then more and more quickly, all the others moved away until finally I was the only one left. This gave me a certain novelty status, I felt, and I was frequently asked to sing a Polish song at a concert or recite a poem at the summer fete.

The holidays were trickier. Six weeks in the summer is a long time for an eight year old to be left virtually alone. But I was fine.

Very recently my seven-year-old granddaughter was working on her school project on the subject of “Seventy” and she asked me what the main difference was between being seven now and when I was seven. There were too many differences to list, but the one main difference I told her about was the freedom I was allowed.

I played all day outside, in the fields and in the woods. I picked flowers and blackberries, I fished in the

canal, I made friends with the horses in the field opposite the coal store. I went everywhere unaccompanied on my bike, or I walked.

I remember once my mum sent me to The Ship (then a shop) to buy 14lbs. of potatoes. The woman in the shop asked me how on earth I planned to carry them back, but I’d thought of that and taken an old pushchair with me. I learned independence very early.

Life in the hut

This hut is identical to the one we lived in. We were at the right hand end. That door was the only entrance. It went directly into the kitchen area. The sink with a cold-water tap was in the corner on the right. Where you can see the first chimney is roughly where that room finished. Below was the iron coal fired stove - we bought coal from the coal heap at the entrance to Site 8.

I can't remember if anyone else had water in the camp but I'm pretty sure we weren't the only ones. We were in no way special. I suspect that all the prefab buildings such as ours were once used as one building with bunks at either side for sleeping in. Therefore the water only needed to be at one end. Probably all those buildings had water at one end. The buildings we called ‘barrels’ (Nissen huts) were much more basic.

The whole room that you entered through the hut door was the kitchen, housing the iron stove and a sink. I think my mum prepared the food on the table which was later cleared and used to eat at. Often in the summer, or when we were short of coal, she used a paraffin stove to cook on - like a camping stove but a bit taller. It must have been so dangerous, I remember her frying chips on it. I think the iron stove had a built-in oven (not sure if it had a heat control) because I do remember her baking a ‘babka’ quite often, a sort of cross between a cake and sweet bread. We loved it but it was a real treat. Most things though were cooked, stewed, on the top of the stove rather than oven baked.

We had a built-in cupboard which was used as a joint larder and storage for plates, pots and other kitcheLidia and Krystyna outside a n utensils. I suspect wealthier residents bought sideboards, etc. as and when they could afford it. The floor was covered in lino.

There was no fridge but in the 1950s that was not unusual in working class Britain. Milk was delivered daily by a milkman, bread lasted a day or two, similarly meat, which was not eaten daily, again not unusual. Things were kept in covered and closed containers because, as you can imagine, living in the country, there was always a problem with rodents - we always had a cat.

There was an internal door to the right of the stove which went through into Lidia’s and my bedroom. To the left of the stove was another door which led to a tiny room with a small, round coal burning stove in the corner. That room had a dining table and chairs in it (I can't remember us using it, I think it was for guests, we always ate in the kitchen). There was another door through that room which led into the bedroom my mum slept in. The rooms had partition walls and were not divided by curtains.

In the middle of the hut the space was slightly smaller which I suppose is why it was lived in by a couple with no children. I think the other end of the hut was a mirror image of ours. Near our house was one of the ‘barrel’ barracks. It was locked and several families used it for storage, often for huge sacks of potatoes which they picked from nearby farms during the harvest.

Reduced circumstances

The picture of us among the flowers was taken outside a neighbour’s hut as there were no flowers outside ours, although we did have an allotment where my mum grew vegetables.

Many of the photos were taken to be sent to relatives back in Poland. Although there was no shame involved in the huts, the Poles had no wish to show family where they now lived. A lot of the Poles there, like my mother's family, especially the ones who came from Eastern Europe via Siberia were landowners. By this I don't mean they were particularly rich, but they had a lot of land; they were definitely now living in reduced circumstances.

One of the quotes in the book says that life for children at the camp was "magical". Maybe for some - for us it was hard. To say we were poor is to massively understate. We often ate potatoes in some form or another because they were the cheapest thing you could buy. Everything was bought on hire-purchase, energy bills were paid off in instalments. The coal lorry was our removal van.

Family christening of Halina Ruszel. Back row from left: Jozef Sarafin (brother of Kazia Ruszel), Wladyslawa Bis (holding baby), Kazia Ruszel (mother of baby), Leopold Bis, Franek Ruszel (father of baby). Front row from left: Jurek Ruszel, Krystyna Pa

Family christening of Halina Ruszel. Back row from left: Jozef Sarafin (brother of Kazia Ruszel), Wladyslawa Bis (holding baby), Kazia Ruszel (mother of baby), Leopold Bis, Franek Ruszel (father of baby). Front row from left: Jurek Ruszel, Krystyna Pa

There was a certain hierarchy at the camp. The fact that most of the men at the camp, mainly due to the language barrier, now worked as manual labourers did not change this at all. They were still very proud. As a widow with two young children my mother came pretty low down in the pecking order.

My sister was 15 when we left the camp and her memories of it are very different to mine. As an older child and then a teenager she was probably more aware than me of the difficulties my mother had to overcome just to survive.

My uncle, Franek Ruszel, worked in the cement factory in Pitstone. He saved all his wages and worked extra shifts (including Christmas Day which paid double the hourly rate) and as soon as he could, along with many other men at the camp, bought one of the new houses on the housing estate between Dunstable and Luton.

It was a typical English suburban house with a tiny kitchen. I think it cost £2000. I remember visiting them while we still lived in

Marsworth and being jealous of the space and cleanness of the place. Those houses seemed like palaces to me then.

There was a shop at the camp, located in the field opposite the social club, (Long Marston Road) before the bridge and Ship Lane. I think it might have been just past the garage (back then a petrol station and shop for spares - I remember being sent there once by my uncle to buy a bicycle repair kit. I had no idea how to say that in English and my uncle had told me to say "reperoofka!" which I did - the man in the shop understandably looked back at me completely bewildered).

That was probably when I was about six but the Polish grocery closed a long time before then. After that (and maybe before) a man with a van came to the camp on a weekly basis. He sold most things and at the beginning also would send parcels back to Poland. Most people bought the imported Polish brands including (and most importantly) a deli range of Polish sausage. He was consequently known as the ‘kielbasiasz’ (sausage man). As the camp began to empty, he only came briefly to the camp and then drove on to Dunstable to sell to the Poles who had moved there. He would often then give us a lift to Dunstable, with my mum sitting in the front with him and my sister and I sitting in the back of the van with the sausages!

Leaving the Hostel

We were at the Hostel until I was nine. By then the Hostel was totally deserted apart from us and one other family – Mr. and Mrs. Zelazny and their son Janusz who was about 13. The Council was eager to close the camp and we were on a waiting list for council housing in Berkhamsted where my mum still worked. I think it was about a week after my birthday that the offer of a house finally arrived. The local coal merchant who also acted as a removal company moved us (in his coal lorry) to Berkhamsted at the end of November. The Zelazny family also moved to Berkhamsted about a week later and the camp finally closed on 4th December 1961.

Lidia Parkitna (now Lidia Eccles)

Lidia, the elder sister of Krystyna Parkitna, was sent a copy of the Marsworth

Polish Hostel book in December 2022 In it she spotted a photograph labelled ‘unknown wedding’, and she was able to identify the people in it, including herself.

Lidia was then able to send us some of her own reminiscences of the Hostel,

with photos. .

I was born In Zambia In Lusaka In 1946 (it was Northern Rhodesia back then).

My mother and her family were taken to Siberia to the work camps. She ended up in Zambia, and then was taken to England in 1948.

I arrived with my mother at the hostel in 1948 and I was two years old, so I was a child the whole time I lived there.

I went to Marsworth School when I was five;

I remember I walked there on my own on my first day. The headmistress was Mrs Pennicot and she had two enormous dogs which I was terrified of.

Then I went to the convent school in Tring when

I was 7, I think. I attended that school until I was 12, then I went to The Grange in Aylesbury. When we moved to Berkhamsted I attended Ashlyns School, but only for two terms as I left school when I was 15½.

Life in the hut wasn’t easy. There were no toilet or bathing facilities or hot water. The toilet block was quite a way from our hut.

There was a stove in the kitchen (what we called the kitchen) which my mother cooked on and kept the house warm. There were three other rooms, two biggish ones which were used as bedrooms and one small one with a small stove.

My mother was a widow so she had to go to work; my sister Krystyna and I were at home on our own mostly. I remember during the holidays cooking chips for our lunch on the Primus stove in a saucepan full of oil.

But living out in the country as a child was fun. We were always outside playing, making camps in the trees and climbing them, picking flowers and blackberries. We also enjoyed playing on the (air raid) shelters and sliding down them, playing round the canal and the reservoir and riding my bike.

There was a cinema where they showed films on a Sunday night - mostly cowboy films. We put on shows there, when the children would do Polish dances, sing Polish songs and do plays. I was in all of these shows.

We moved to Berkhamsted in November 1961 and I was 15 in September.

Aniela Parkitna, née Ruszel

We are grateful to Lidia Parkitna for sending us this graphic, moving and informative account of her mother

Aniela’s journey from Poland to Marsworth Hostel

The following is a paraphrased translation of an account written by Aniela Parkitna, then aged 84,

to her daughter Lidia Eccles, outlining briefly the events which led to her leaving Poland in 1940

and being transhipped across Russia and the Middle East to

Northern Rhodesia in Africa and thence to England.

Translated by Lidia Eccles. Recompiled and annotated by Christopher Eccles

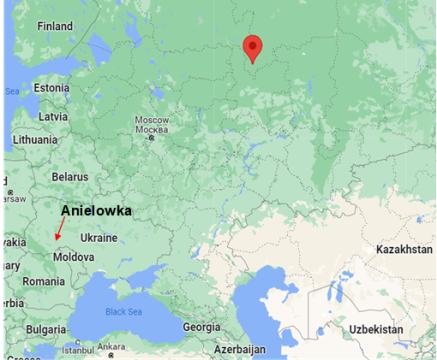

My name is Aniela Parkitny. I was born in Poland in 1909. Until 1940 my family owned and farmed land at Anielowka, which is a village close to the town of Ternopol in the south-east of Poland. The Ukrainians thought that part of Poland was theirs.

On 10th February 1940 our village was invaded by the Army. They came on sledges and there were Ukrainian soldiers and Russian soldiers.

They ordered everyone to pack their things and told us we were leaving. All the houses were set alight and the horses and other animals burned. Also the old people and children were told they were to leave. My sister, Albina, was allowed to stay because she was married to a Ukrainian – Stalin had signed a pact with Hitler and they had agreed to divide up Poland between them . All the native Poles were to be driven out. Ternopol is now in the Ukraine.

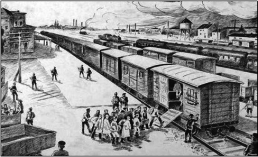

We were all packed into a train of cattle wagons and we set off on a very long journey. The journey lasted for three weeks and we eventually arrived at a place called Murashin (called in Russian ‘Murashi’, on the fringes of western Siberia. CE).

We were herded onto sledges and carried for another 100km to a place called Noshul. It was freezing cold and there was thick snow.

At Noshul there was a lumber camp. Timber was cut and hauled (probably to supply mining props – much coal was, and still is, mined in this region. CE).

There were cabins for us to live in, and at least these were warm. There was, of course, much wood to burn and we had fires in the cabins. The beds in the cabins were made from wooden boards but we had no actual bedding to sleep on. We were given 300g of bread per day each and boiled water to drink with it. We were left for one week doing nothing at all and then the men were made to go and cut the timber while the women had to split the logs and also keep the snow cleared from the roadways so that the tractor could come in and haul the logs.

When the summer came, the women’s work was lopping the small branches from the felled trees and cutting logs into one-metre lengths with big saws.

There was an epidemic of typhoid fever in the camp. One cabin became a makeshift hospital. I became very ill with the fever and many, many people died. Every time a Polish person died, the Russian nurses would laugh and say, “Ah well, he’s gone back to Poland.”.

(On 30th September 1941 Hitler broke his pact with Stalin and invaded Russia. The exiled Polish Head of State, General Sikorski, sent a message to Stalin from his London HQ requesting that all Polish prisoners be set free to fight alongside the Allies. CE).

We left Noshul. My sister Maria and her family stayed, saying that they hoped to return to Poland. I never saw them again until 1964. When I went to visit Poland, I met Maria and some of her surviving family there.

My father Valenty and my mother Anna left Noshul with me. All the fit men were conscripted into the army to fight Hitler.

It took us two days to walk the long way back to Murashin, pulling a sledge which we had packed with our few things and some dried mushrooms and berries to eat. We arrived at Murashin at night, and I was so tired that I was falling asleep standing up. We all waited in a big hall and slept. In the morning we were again herded into wagons, supervised by the Russians.

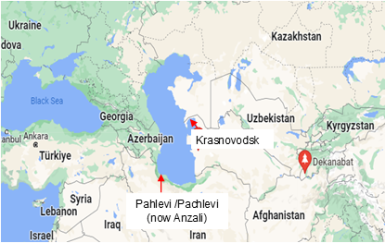

We were then taken on a train journey for between three and four weeks (I am not sure) to a place in Uzbekistan called Dekanabat. My sister Zuzia was taken somewhere else and I have never seen her again. She and most of her children died somewhere in Uzbekistan.

There were many Jewish people with us at Dekanabat. We lit fires and cooked grain to eat. Some Uzbeki people came with horse and donkeys and said that they were for the Polish people only. We were told we were leaving. Those without horses had to walk.

We went on our way and walked all night to a large farm complex where we were told we had work. We were put into stables to live. They had been cleaned out and we had fires to keep warm.

It was Christmas Eve 1941, and we were all sitting round fires on the floor. Some were crying – many sang carols. My mother, Anna,

was very ill with dysentery but still managed to prompt others when they forgot the words of the carols or songs. On Christmas Day we were taken to the ‘boss’; who gave us 300g of flour each. The

next day my mother died of the dysentery in my arms. We wrapped her body in sheets and buried her in the Uzbeki cemetery.

I also had the dysentery and I expected not to live but, again, I was lucky and recovered.

We worked on the farm until March and then typhoid fever broke out and almost everyone was very ill. My father Valenty died soon after this.

I caught the typhoid and I was in a coma for four days. I remember coming round lying on hay in the corner of a barn and I realised I had recovered but could not use

my legs. One of the other women used to pull me out into the sunshine to warm me during the day and then pull me back in at night.

That same woman’s son went into Dekanabat to see the Polish doctor there who gave him some ointment. I rubbed this on my legs and I was eventually better.

In the spring of 1942 we were still all working on the farm, picking pests off the grain crops by hand. We each had a sieve and a grain ration of

1 litre each. But we were also sieving grain as part of our work and much grain got stolen by all of us and used. We had the use of a mill on the nearby river and could make flour and cook placki (pronounced ‘platzki’, resembling an Indian chapati bread. CE) to eat.

In June 1942 we heard from the Polish doctor in the town that we were to be moved again. Sure enough, in July we were made to walk to Dekanabat and assemble in the barracks there. Most of the Polish soldiers had died of dysentery but some remained. While in the barracks there was an outbreak of malaria. We all caught this, but luckily, a Polish nursing sister gave us quinine and we did recover. We had to register for transhipment and there were huge queues

to do this.

When we had registered, we were taken to the station to catch a train for Krasnovodsk but we spent three weeks on the station platform camped out waiting for the train to come. The train, when it came, took us to Krasnovodsk in western Uzbekistan.

We boarded a boat from there and sailed across the Caspian Sea to a place called Pachlevi. There were Polish soldiers protecting (guarding) us on the boat and we all had to pretend to be well even if we were ill because we had been told that only the well ones would be taken any further. At Pachlevi we were handed over to the British authorities (Pachlevi was in Persia, now Iran, and whilst officially neutral, the Shah was sympathetic to the Allied cause. CE) and told that we were subject to English law. While the soldiers took the ill people away to hospital, we bathed in the Caspian Sea and were very happy at this time. We all got food and tasted meat for the first time since the invasion of our village. It was lamb and we were so unused to it that we all got terrible stomach aches!

We were in Pachlevi for two weeks and then we boarded trucks for Tehran, the capital. We had mattresses and food. We cooked traditional Polish food including kluski (a form of pasta, CE) and we had apples and good bread. We also received parcels from America with dresses, shawls and blankets. I cannot remember how long we were in Tehran but I think it must have been about a month.

From there we went to a place called Ahvaz and we lived, again, in stables for about three weeks while we waited to board the boat which would take us all to Africa. There were stories going round that the sea was mined and that this was a very dangerous journey. We were all quite scared about this. When the time came to board the ships, I was among those on the very first ship to leave. We had four other boats escorting us and the crossing was without incident. (It is highly probable that the Straits of Hormuz were, in fact, mined to prevent Allied oil shipments leaving Basra and that the ‘four other boats’ were RN minesweepers based in the Gulf. CE)

We stayed in a hostel outside Lusaka which was for Polish people only. We saw homes of many English people who seemed to be very rich. In the hostel there was one hut for every four people, and we had a communal kitchen and four dining rooms. The huts were made of a sort of brick made from mud with straw roofs. During my stay in Lusaka, I caught malaria again, twice. I worked in a hospital, sewing up sheets and doubling sheets.

Later I met an Italian man who had been a prisoner-of-war and we fell in love. Our daughter Lidia was born on 2nd September 1946 in Lusaka.

The Polish soldiers fought for the Allies on every front but they died for nothing. Poland was partitioned and there was a communist government installed. All the Polish people in the hostel vowed never to return until Poland was again free.

Churchill had agreed to accept Polish refugees: some to England and some to Australia. So in 1948 I arrived in England with my daughter. We arrived in October and went to a place called Daglingworth in the north of England to stay in a hostel there. Lidia got very ill with bronchitis.

We soon moved to another settlement in Marsworth, near Tring in Hertfordshire in the southeast of England. There I met and married Jozef Parkitny who was a Polish soldier, injured in the war and living in London near Baker Street. Here I also met up again with my brother Franek, who had been in the army.

My younger daughter Krystyna was born on 9th November 1952. In 1955 my husband Jozef died from leukemia.

I worked in nearby Berkhamsted, sewing coats in a garment factory.

In 1961 the Polish hostel was finally closed down and I moved into a council house in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire.