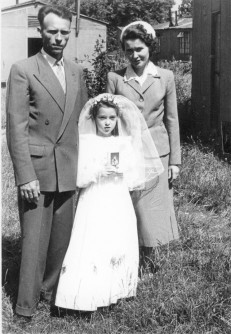

Bronislawa Glinska and Family

We are grateful to Jo Glinska for supplying much valuable information and photos of her parents, Bronislawa and Michal in 2019.

The account by Bronislawa of life at Marsworth Hostel is especially interesting and descriptive.

Michal Glinski

The eldest of four brothers, Michał Glinski was born in Dobryniewo near Baranowicze, then in Poland, now in Belarus. Domanowo, the nearest town, had a station on the railway line from Brest to Baranowicze.

At the outbreak of war, when Soviet Russia invaded from the east, schools were suspended and Michal began working on the railways at the age of 16. This was a useful and non-threatening profession, which may have spared him deportation to Siberia.

After the Germans invaded from the west in June 1941, Michał was taken from his home one night by Soviet partisans who wanted to increase their numbers. This immediately put his whole family at risk of execution by the Germans. After less than two weeks Michal managed to escape and return home, but the Germans had heard about his time with the local partisans. Managing with the help of the other villagers and local 'Mayor'/Commissar to convince the Germans that he was an unwilling participant in partisan activities, Michal resumed working on the railways.

Around two years passed, and then he was sent with 11 other workers to occupied France to help with repairing the railways which were being heavily bombed. One evening the group of Polish railway workers were eating in a bar adjacent to Besancon station in eastern France. They were approached by a Polish speaking 'French' man, and asked if they would like to join the local resistance. After 24 hours all 12 gave their answer, and joined the French partisans in their fight against the Germans.

Michal was involved in the harassment of retreating Germans near the Swiss border with France, and the liberation of Pontarlier on 5th September 1944 when the partisans and the advancing US 45th infantry forced the Germans from that area of France.

Michał then had the opportunity to enlist in the Polish Army, which had fought its way upwards from the south to the north of Italy where Michal joined them. After training as a commando, he saw action at the Senio River and Bologna. He was subsequently awarded the Polish Army Medal and Cross of Valour.

Members of the Polish Army were unable to return to Poland for fear of their lives under the Soviet occupation. The British government arranged for them to be brought to Britain and that is how Michał came to Britain and eventually to Marsworth.

Although he was able to contact his family and let them know he was safe, he did not meet his brothers again until 1977 on a hastily arranged trip to Warsaw. He returned to Belarus in 1997, his only visit since the war.

Marsworth life by BRONISLAWA GLINSKA

(Née BAZAN)

Background

I was born in eastern Poland, as were my parents and countless earlier generations of my family. We were smallholders in Dabrowo, near Sokal, and I was one of eight children. Early in WW2 we were forcibly taken by the Russians from our home to Siberia, because we were ‘kulaki’, or landowners. We were put to work felling trees in the huge forests there, and our land was forfeited.

After two years in Russia there was an ‘amnesty’ for us - we were to be allowed to leave and go south to where a new Polish army was forming in Uzbekistan. Around two million people were deported to Siberia, but only around 170,000 left. A great many, including my parents, one brother and a sister, died there from the harsh conditions, but some chose to stay and their descendants still live there.

In 1942 we left Uzbekistan via the Caspian Sea, and went to Iran. The government and people there were very kind to us. From Iran we went on to British colonies in Africa, which along with India and Mexico took in the majority of civilian refugees. The Polish army was by this time already fighting at the front along with the British army. I spent the remainder of the war years in Ifunda camp, Tanganyika in Africa, with my elder sister Aniela.

England - Marsworth

In 1948 I left Africa for England. As an underage orphan, I had priority and travelled alone on the Carnarvon Castle from Mombasa, arriving at Southampton Docks in May. My sister, being an adult, followed later. Refugees were accommodated in former American air bases, my allocated home for the foreseeable future was to be Marsworth camp (Site 7). As far as I can remember there were only Polish people there.

It was not known how long we would stay in Marsworth, but we all soon settled in. Nearby we had Tring and Aylesbury, and there was plenty of beautiful countryside. I particularly liked the canal and reservoirs.

Mama by the lock - unfortunately she doesn't remember exactly where the lock was, but it would have been quite near the camp itself. The main reason for taking the photo was to record the first wearing of her new dress - she was absolutely delighted with it, thought it was gorgeous. It came to her courtesy of an American Red Cross parcel, so very belated but heartfelt thanks to the fashion conscious and generous lady who donated it.

Life in the camp

The camp itself was very homely. The little huts, divided between numbered sites, housed two families each. Some were semi-circular Nissen huts, but ours was just an

ordinary hut. We affectionately called them ‘barrels of laughter’, I remember that people really liked living in them and there was a great community spirit in the camp. After Africa, though, it

seemed very cold –

I had brought many books with me to England and had to burn them all to keep warm. Mainly, the huts served us very well. They were not luxurious but certainly comfortable, furnished with

iron-framed beds, a table and chairs, wardrobe and stove.

Anything else we needed could be obtained in the second-hand shop at Tring, or improvised.

We had a ‘coffee table’ converted from a wooden packing crate.

At first meals were cooked in communal areas, but gradually people began to cook for themselves. Bathing and laundry were also communal, there were huge water containers in the camp. Everything was rationed; we all had cards and supplies were brought into the camp weekly from Tring. No-one went short of anything; we had enough to eat but it was very plain food. There was no waste, a use was found for everything.

After a while, we began to establish gardens around the huts. We grew vegetables but some flowers too, which helped the residents feel at home. A lot of us had come from rural backgrounds, so we enjoyed tending our gardens.

Life in the camp was very well organised, and run very much with the wellbeing of the residents in mind. There was a church (chapel), a Polish doctor, and infirmary. Patients who were seriously ill were taken to local hospitals in Aylesbury – the Tindal and Royal, I think.

Young people often spoke ‘school’ English, I learned a little in Africa. It was sufficient so that they could continue their education if they were in a position to. There were also English courses available generally.

For children, there was a choice of the local school, or a private school in Tring. For the very small ones, there was a nursery school. A large library was also provided for everyone to use. Gradually, improvements were made in all aspects of everyday life, and we all helped each other.

Work and transport

Immediately after the war we received ‘pocket money’ if unemployed. Officials came to the camp with details of local job vacancies, any work offered was gladly accepted. We knew we had to make our own way and we wanted to settle down, have families and all the usual things in life, so we tried to save as much as possible.

Some professional people, like doctors, nurses or teachers, had to do courses so that they could follow their profession in England, but after the war there were many jobs available for unskilled workers as well.

My husband (Michal) had worked on the railways during the war, so he got a job with British Rail. I worked in a factory;

I was a child when the war broke out and unskilled. My sister had been housekeeper to a doctor and his family in Poland but never managed to learn much English, so became a housewife.

Not many people in those days had cars, so to get to work we would take the train from Tring or a local bus, cycle, or walk. Michal cycled to work but later on he learned to drive. Our neighbour by this time had bought a second-hand car, and sometimes gave us a lift to work or the shops.

From left to right, my Mum's brother Mietek Bazan and his wife Stasia, who was my Mum's best friend back in Poland. They would have been visiting, as they lived in Trowbridge, Wiltshire. Then my Mum and her sister Aniela and brother-in-law Bronek Witczak.

From left to right, my Mum's brother Mietek Bazan and his wife Stasia, who was my Mum's best friend back in Poland. They would have been visiting, as they lived in Trowbridge, Wiltshire. Then my Mum and her sister Aniela and brother-in-law Bronek Witczak.

Good neighbours and good times

Even if you worked, there was little spare money for outings. Our English neighbours were well-disposed and friendly to the camp’s residents, they understood our situation although I don’t remember anyone visiting us. Young people did go to the local pubs sometimes, everyone behaved well and there was no friction that I can recall.

There were Saturday cinema visits to Aylesbury, returning by bus to Tring then on foot to Marsworth using the canal towpath. There were shopping trips by train to Watford or even Oxford Street, as well as organised theatre outings, but not very often.

Mainly our entertainment was more informal. We socialised within the camp, and there were football matches as well as Saturday dances which drew people from neighbouring camps such as Leighton Buzzard or even London and surrounding areas – there were many attractive young ladies in the camps.

Also there was the ever-popular walk in the local countryside or by the canal, wondering at the fishermen sitting patiently on the banks with their lines. On Sundays there was a well-attended church service, and traditional Polish occasions such as 3rd May were always celebrated with great ceremony.

Leaving Marsworth

People felt happy and safe at Marsworth, it was a good, peaceful life but we all knew we had to concentrate our energies on the future. The camps

were gradually closing, we had been at Marsworth several years by now. We had jobs, friends, and links with the wider community.

Those who were able to, left before the official closure of the camp. Those in difficult circumstances were helped by the Council to find other accommodation. For most of us, our place of work decided where we would live. That meant Luton for my family. We managed to find a house which would suit all of us, including my sister and brother in law. It was old and quite dilapidated, but we were very practical and happy to do most of the renovation work ourselves.

On leaving that quiet, homely place Marsworth, where we had been so happy and settled, everyone experienced a certain regret. Even years later, on meeting friends who had been at the camp, we would still speak with great affection and nostalgia about the time when we lived in the ‘barrels of laughter’. It was such a close community, many of us stayed in touch and lived within easy reach of one another.

There are still some of us living in and around Luton, Dunstable and surrounding areas, as well as our children and their families. It should be remembered that the post-war years were very hard for everyone. Britain was devastated by the war, yet found room for thousands of us who needed help and refuge. For this we were, and are, very grateful.

Translated/transcribed from a Polish handwritten account and verbal additions by Jo Glinska, daughter, 04/06/19.