Wladyslaw Szyszko

Our story starts at the end of World War One when Poland became an independent state following over 100 years of being partitioned between Prussia, Russia and

Austria. In

1919-1921, Poland fought and won a war against the emerging Soviet Union and established her eastern border about 150 miles to the east of where it is now on lands that had historically formed part

of Poland.

The Polish government encouraged soldiers who fought in that war to settle in the east of the country by offering them plots of farmland to help establish the revived Polish nation. Wladyslaw Szyszko’s parents, Karol and Rozalia, were two of these settlers, being rewarded with a 40 hectare farm in a village called Wołowiel, which is shown on the modern map in red.

Wladyslaw was born in 1927. He had three brothers: Antoni, Wiktor and Piotr and a sister Jadwiga. Their peaceful life in the countryside was shattered by the outbreak of war in September 1939. A few days after Hitler invaded Poland from the west, Stalin invaded Poland from the east in a secret pre-arranged plan to divide Poland between them. Worse followed in February 1940 when the Soviet Union took action to destroy the Polish state by deporting to Siberia anyone considered a threat to them. These included the military, teachers, civil servants and settlers. With a few hours notice, whole families were told to pack and were loaded onto cattle trucks heading for forced labour camps in Siberia. Between one and two million people (estimates vary) were affected, but many tens of thousands never got as far as Siberia. Many military officers were murdered in cold blood and many other people died on route to Siberia in the harsh conditions.

At just 12 years old, Wladyslaw and the rest of his family were sent to Siberia and he was put to work straight away sawing wood in bitterly cold conditions for export to Germany. Work only stopped when the temperature dropped below minus 50. Many died through cold and disease. Their eyesight became poor in low light because of vitamin deficiencies.

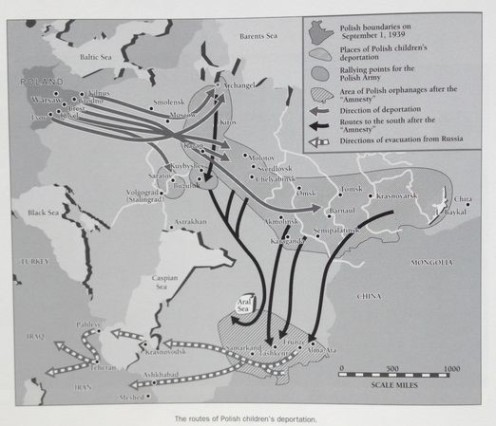

This harsh life continued until the spring of 1942 when the captive Poles were freed. This was the result of negotiations between the Allies and Stalin following Germany’s attack on Russia in the previous year, which agreed to form a new Polish Army in Persia under the command of General Anders. Although now free, the Poles had to make their own way south to Persia. Many remained, many died on route. Of the million or so Poles that were deported to Siberia, just over 100,000 made it to Persia. Some of the routes taken are illustrated in the map.

Wladyslaw travelled through Kazakhstan and Tashkent in Uzbekistan to Pachlevi in Persia. As they travelled south they were able to start to supplement the poor diet they had had in Siberia with mulberries and apricots, but they also caught diseases like malaria and had no quinine to treat it. This did not clear properly until an improved diet improved their general health. Many also died of dysentery.

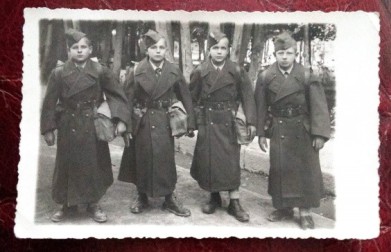

After reaching Persia at the age of 15, Wladyslaw joined one of several Polish army cadet schools there. These schools were moved to Palestine, then under British control, where he resumed his education. There was also a Polish girls’ school in Nazareth.

The cadets were issued with British Army uniforms with Polish army badges like the ones shown here. He continued his education there and later worked on repairing British army vehicles in Sarafand (in present day Lebanon).

While Wladyslaw was studying in Palestine, his eldest brother and his father fought in the Polish army in North Africa and in Italy. His brother was awarded the Virtuti Militarii medal, the highest Polish award for bravery for his role in the decisive battle at Monte Cassino in Italy, which led to the fall of Italy.

In 2003 the Polish Government created a medal for survivors of the exile in Siberia. Wladyslaw was presented this medal by the Polish Embassy.

While he was in the Middle East he was also able to visit Cairo, the main purpose to visit his father, who had been wounded in action in North Africa and was recovering in a Polish military hospital. Wladyslaw continued in Palestine until 1947 when the state of Israel was formed and the British pulled out of the country. Several thousand Polish Jews were allowed to desert the Polish Army and stay in Israel, but many other Jews lost their lives fighting in the Polish Army in Italy as is evidenced by the graves in Polish military cemeteries in Italy.

When the British left Palestine in 1947 they took the Polish army and the cadets with them to Britain, arriving by ship at Southampton. Wladyslaw spent his first couple of months in England in a British army camp at Hursley between Winchester and Southampton. He was then moved to Salisbury for a year and to an air force camp in Newquay where he was demobbed. The photo, taken in 1949, shows him aged 2l, in his demob suit. He was also given a hat, a shirt, a pair of army boots and a greatcoat.

He was now ready to start a new life working in England. It was not possible to return to Poland, which was now dominated by Russia and the communist party. Anyone who had been a member of Anders’ Army would be treated like a second class citizen or worse, and he had already had a taste of what that could be like in Siberia. Moreover, the village he grew up in was no longer in Poland. With the changes to borders made in the post-war settlement, it was now part of the USSR.

Wladyslaw did return in 1991 for a visit following the fall of the communism. He travelled with his second wife by coach and it was a very emotional experience. His impression was of a corrupt and very run down country, set back “by a hundred years because of communism”. Everything was neglected and no one seemed to care about anything, particularly in the former German territories in the west that had been given in the post-war settlement as compensation for the lost territories in the east.

Everyone was frightened to invest for fear of the Germans returning some day.

Wladyslaw’s first job in England was working on a farm with other Polish people using a digger and loading soil onto a lorry. While he was there, he broke his leg playing football and it was slow to heal taking three months. As a result of this he lost his job, which was taken by another Pole.

At this point Wladyslaw moved to Marsworth because his parents were already there, having arrived from Beirut in the Lebanon. He then used his engineering training to get a job in Dunstable for a company developing and building tools and machines for building cars. The company was eventually taken over by Honda. After 29 years working for the same company, Wladyslaw was made redundant. He was offered a job in Hemel Hempstead at a contact lens factory by a friend who was a manager there and had previously worked with Wladyslaw in Dunstable, again building precision machines for the production line..

One of the biggest problems for Wladyslaw when he first came to England was the language. He went to college in Aylesbury after work for two years to learn English. He was also used to metric measurements and had to learn imperial measurements for his work.

The Polish Catholic church in Dunstable used to be a Protestant church, but when it became redundant it was offered to the Polish community at a reduced price. Wladyslaw was on the committee that organised the purchase of the church.

Wladyslaw was the last person to leave Marsworth Camp when he moved to Pitstone in 1964. Five or six other Polish families from Marsworth camp lived and worked in Pitstone and Ivinghoe, many as builders. Nina (Janina) Baliszewska and Wielgomas remain. Other families that lived in Pitstone were Rochel, Bis and Łatyszonek.

Wladyslaw, Rozalia and daughter in the garden of their first house after they left Marsworth Hostel.

Wladyslaw, Rozalia and daughter in the garden of their first house after they left Marsworth Hostel.

Wladyslaw and Anna used to maintain the 17 Polish graves in Marsworth churchyard but about three years ago they had to give this up through ill health. The unmarked grave is of Janina Puszczyńska and her husband Gordon (?). She was a Polish aristocrat who worked for the Red Cross during the war. When she came to Marsworth it was the first time she really mixed with ‘ordinary people’, and she said “She never realised that ordinary people were so good.” She could speak English and French very well. She had a daughter who became a doctor in London.

Wladyslaw met his first wife (Rozalia Dziadura) in Marsworth Camp. Rozalia was sent to Siberia when she was only three years old. Her mother died there, but Rozalia made her way to Persia with her sister.